Nest Site Selection during Colony Relocation in Yucatan Peninsula Populations of the Ponerine Ants Neoponera villosa (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ant Collection and Identification

2.2. Nest Site Selection

2.2.1. Experimental Setup

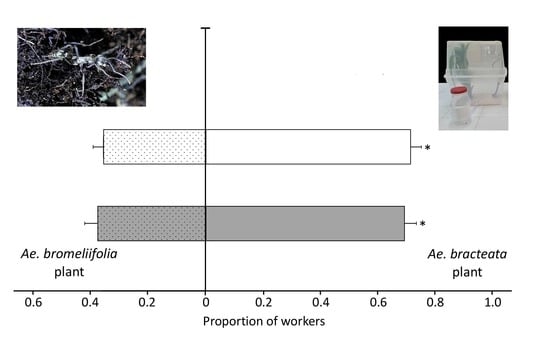

2.2.2. Experiment One

2.2.3. Experiment Two

2.2.4. Experiment Three

2.2.5. Experiment Four

2.3. Statistical Analyses

2.4. Ethics Statement

3. Results

3.1. Species Identification

3.2. Tandem Running Behavior

3.3. Nest Site Selection

3.3.1. Experiment One

3.3.2. Experiment Two

3.3.3. Experiment Three

3.3.4. Experiment Four

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McGlynn, T.P. The ecology of nest movement in social insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2012, 57, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pratt, S.C. Nest site choice in social insects. In Encyclopedia of Animal Behavior, 2nd ed.; Choe, J.C., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; Volume 4, pp. 766–774. [Google Scholar]

- Tschinkel, W.R. Nest relocation and excavation in the Florida harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex badius. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, B.; Paul, M.; Sumana, A. Opportunistic brood theft in the context of colony relocation in an Indian queenless ant. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Visscher, P.K. Group decision making in nest-site selection among social insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2007, 52, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, D.M. Nest relocation in harvester ants. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1992, 85, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, N.E.; Gordon, D.M. Seasonal spatial dynamics and causes of nest movement in colonies of the invasive Argentine ant (Linepithema humile). Ecol. Entomol. 2006, 31, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlynn, T.P.; Dunn, T.; Wayman, E.; Romero, A. A thermophile in the shade: Light-directed nest relocation in the Costa Rican ant Ectatomma ruidum. J. Trop. Ecol. 2010, 26, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Möglich, M. Social organization of nest emigration in Leptothorax (Hym., Form.). Insectes Soc. 1978, 25, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, J.-W.; Lee, C.-Y. Induced disturbances cause Monomorium pharaonis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) nest relocation. J. Econ. Entomol. 2015, 108, 1237–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, J. The effect of shade and competition on emigration rate in the ant Aphaenogaster rudis. Ecology 1982, 63, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droual, R. Anti-predator behaviour in the ant Pheidole desertorum: The importance of multiple nests. Anim. Behav. 1984, 32, 1054–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahbi, A.; Retana, J.; Lenoir, A.; Cerdá, X. Nest-moving by the polydomous ant Cataglyphis iberica. J. Ethol. 2008, 26, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McGlynn, T.P.; Carr, R.A.; Carson, J.H.; Buma, J. Frequent nest relocation in the ant Aphaenogaster araneoides: Resources, competition, and natural enemies. Oikos 2004, 106, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlynn, T.P. Ants on the move: Resource limitation of a litter-nesting ant community in Costa Rica. Biotropica 2006, 38, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smallwood, J.; Culver, D.C. Colony movements of some North American ants. J. Anim. Ecol. 1979, 48, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela-González, J.; López-Méndez, A.; García-Ballinas, A. Ciclo de actividad y aprovisionamiento de Pachycondyla villosa (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) en agroecosistemas cacaoteros del Soconusco, Chiapas, México. Folia Entomol. Mex. 1994, 91, 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lachaud, J.-P.; Fresneau, D.; García-Pérez, J. Étude des stratégies d’approvisionnement chez 3 espèces de fourmis ponérines (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Folia Entomol. Mex. 1984, 61, 159–177. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Bautista, M.; Lachaud, J.-P.; Fresneau, D. La división del trabajo en la hormiga primitiva Neoponera villosa (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Folia Entomol. Mex. 1985, 65, 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Dejean, A.; Corbara, B. Predatory behavior of a neotropical arboricolous ant: Pachycondyla villosa (Formicidae: Ponerinae). Sociobiology 1990, 17, 271–286. [Google Scholar]

- Mackay, W.P.; Mackay, E.E. The Systematics and Biology of the New World Ants of the Genus Pachycondyla (Hymenoptera: Formicidae); The Edwin Mellen Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wild, A.L. The genus Pachycondyla (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Paraguay. Bol. Mus. Nac. Hist. Nat. Parag. 2002, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dejean, A.; Olmsted, I.; Snelling, R.R. Tree-epiphyte-ant relationships in the low inundated forest of Sian Ka´an biosphere reserve, Quintana Roo, Mexico. Biotropica 1995, 27, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, I.O.; De Oliveira, M.L.; Delabie, J.H.C. Notes on the biology of Brazilian ant populations of the Pachycondyla foetida species complex (Formicidae: Ponerinae). Sociobiology 2013, 60, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dejean, A. Influence de l´environnement pré-imaginal et précoce dans le choix du site de nidification de Pachycondyla (=Neoponera) villosa (Fabr.) (Formicidae, Ponerinae). Behav. Process. 1990, 21, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejean, A.; Olmsted, I. Ecological studies on Aechmea bracteata (Swartz) (Bromeliaceae). J. Nat. Hist. 1997, 31, 1313–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espejo-Serna, A.; López-Ferrari, A.R.; Ramírez-Morillo, I.; Holst, B.K.; Luther, H.E.; Till, W. Checklist of Mexican Bromeliaceae with notes on species distribution and levels of endemism. Selbyana 2004, 25, 33–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, W.M. The ants of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. Part I. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 1908, 24, 399–487. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, F.H.; Lachaud, J.-P.; Pérez-Lachaud, G. Myrmecophilous organisms associated with colonies of the ponerine ant Neoponera villosa (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) nesting in Aechmea bracteata bromeliads: A biodiversity hotspot. Myrmecol. News 2020, 30, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzing, D.H. Vascular Epiphytes. General Biology and related Biota; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Beutelspacher, C.R. Bromeliáceas como Ecosistemas, con especial referencia a Aechmea bracteata (Swartz) Griseb; Plaza y Valdés ed.: México DF, México, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Galindo-Leal, C.; Cedeño-Vázquez, J.R.; Calderón, R.; Augustine, J. Arboreal frogs, tank bromeliads and disturbed seasonal tropical forest. Contemp. Herpetol. 2003, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hénaut, Y.; Corbara, B.; Pélozuelo, L.; Azémar, F.; Céréghino, R.; Herault, B.; Dejean, A. A tank bromeliad favors spider presence in a neotropical inundated forest. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e114592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blüthgen, N.; Verhaagh, M.; Goitía, W.; Blüthgen, N. Ant nests in tank bromeliads – an example of non-specific interaction. Insectes Soc. 2000, 47, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaisson, P. Environmental preference induced experimentally in ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Nature 1980, 286, 388–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djieto-Lordon, C.; Dejean, A. Tropical arboreal ant mosaics: Innate attraction and imprinting determine nest site selection in dominant ants. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1999, 45, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djieto-Lordon, C.; Dejean, A. Innate attraction supplants experience during host plant selection in an obligate plant-ant. Behav. Process. 1999, 46, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whigham, D.F.; Olmsted, I.; Cabrera Cano, E.; Curtis, A.B. Impacts of hurricanes on the forests of Quintana Roo, Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. In The Lowland Maya Area: Three Millennia at the Human-Wildland Interface. Gómez-Pompa, A.; Allen, M.F., Feddick, S.L., Jiménez-Osornio, J.J., Eds.; Haworth Press: Binghamton, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 193–213. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, C.R. Nesting space limits colony size of the plant-ant Pseudomyrmex concolor. Oikos 1993, 67, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, C.R. Amazonian ant-plant interactions and the nesting space limitation hypothesis. J. Trop. Ecol. 1999, 15, 807–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.L. Nest site selection and longevity in the ponerine ant Rhytidoponera metallica (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Insectes Soc. 2002, 49, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, H.; Fellowes, M.D.E.; Cook, J.M. Arboreal thorn-dwelling ants coexisting on the savannah ant-plant, Vachellia eriobola, use domatia morphology to select nest sites. Insectes Soc. 2013, 60, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrus, S. The cavity-nest ant Temnothorax crassispinus prefers larger nests. Insectes Soc. 2015, 62, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Franks, N.R.; Dornhaus, A.; Metherell, B.G.; Nelson, T.R.; Lanfear, S.A.J.; Symes, W.S. Not everything that counts can be counted: Ants use multiple metrics for a single trait. Proc. R. Soc. B 2006, 273, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Franks, N.R.; Mallon, E.B.; Bray, H.E.; Hamilton, M.J.; Mischler, T.C. Strategies for choosing between alternatives with different attributes: Exemplified by house-hunting ants. Anim. Behav. 2003, 65, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inui, Y.; Itioka, T.; Murase, K.; Yamaoka, R.; Itino, T. Chemical recognition of partner plant species by foundress ant queens in Macaranga-Crematogaster myrmecophytism. J. Chem. Ecol. 2001, 27, 2029–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, D.P.; Hassall, M.; Sutherland, W.J.; Yu, D.W. Assembling a mutualism: Ant symbionts locate their host plants by detecting volatile chemicals. Insectes Soc. 2006, 53, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürgens, A.; Feldhaar, H.; Feldmeyer, B.; Fiala, B. Chemical composition of leaf volatiles in Macaranga species (Euphorbiaceae) and their potential role as olfactory cues in host-localization of foundress queens of specific ant partners. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2006, 34, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dáttilo, W.F.C.; Izzo, T.J.; Inouye, B.D.; Vasconcelos, H.L.; Bruna, E.M. Recognition of host plant volatiles by Pheidole minutula Mayr (Myrmicinae), an Amazonian ant-plant specialist. Biotropica 2009, 41, 642–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grangier, J.; Dejean, A.; Malé, P.-J.G.; Solano, P.-J.; Orivel, J. Mechanisms driving the specificity of a myrmecophyte-ant association. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2009, 97, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torres, M.F.; Sanchez, A. Neotropical ant-plant Triplaris americana attracts Pseudomyrmex mordax ant queens during seedling stages. Insectes Soc. 2017, 64, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flaspohler, D.J.; Laska, M.S. Nest site selection by birds in Acacia trees in a Costa Rican dry deciduous forest. Wilson Bull. 1994, 106, 162–165. [Google Scholar]

- Dejean, A.; Corbara, B.; Lachaud, J.-P. The anti-predator strategies of Parachartergus apicalis (Vespidae: Polistinae). Sociobiology 1998, 32, 477–487. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, S.C.; Pierce, N.E. The cavity-dwelling ant Leptothorax curvispinosus uses nest geometry to discriminate between potential homes. Anim. Behav. 2001, 62, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonato, V.; Cogni, R.; Venticinque, E.M. Ants nesting on Cecropia purpurascens (Cecropiaceae) in Central Amazonia: Influence of tree height, domatia volume and food bodies. Sociobiology 2003, 42, 719–727. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, C.; Fresneau, D.; Kolmer, K.; Heinze, J.; Delabie, J.H.C.; Pho, D.B. A multidisciplinary approach to discriminating different taxa in the species complex Pachycondyla villosa (Formicidae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2002, 75, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, I.O.; De Oliveira, M.L.; Delabie, J.H.C. Description of two new species in the Neotropical Pachycondyla foetida complex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Ponerinae) and taxonomic notes on the genus. Myrmecol. News 2014, 19, 133–163. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Lachaud, G.; Lachaud, J.-P. Hidden biodiversity in entomological collections: The overlooked co-occurrence of dipteran and hymenopteran ant parasitoids in stored biological material. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ivanova, N.V.; DeWaard, J.R.; Hebert, P.D.N. An inexpensive, automation-friendly protocol for recovering high-quality DNA. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2006, 6, 998–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Larralde, A.J.; Suaste-Dzul, A.P.; Gallou, A.; Peña-Carrillo, K.I. DNA recovery from microhymenoptera using six non-destructive methodologies with considerations for subsequent preparation of museum slides. Genome 2017, 60, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hölldobler, B.; Traniello, J. Tandem running pheromone in ponerine ants. Naturwissenschaften 1980, 67, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresneau, D. Individual foraging and path fidelity in a ponerine ant. Insectes Soc. 1985, 32, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Anoop, K.; Sumana, A. Leaders follow leaders to reunite the colony: Relocation dynamics of an Indian queenless ant in its natural habitat. Anim. Behav. 2012, 83, 1345–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoop, K.; Sumana, A. Response to a change in the target nest during ant relocation. J. Exp. Biol. 2015, 218, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pinter-Wollman, N.; Hubler, J.; Holley, J.-A.; Franks, N.R.; Dornhaus, A. How is activity distributed among and within tasks in Temnothorax ants? Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2012, 66, 1407–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, T.O.; Mullon, C.; Marshall, J.A.R.; Franks, N.R.; Schlegel, T. The influence of the few: A stable ‘oligarchy’ controls information flow in house-hunting ants. Proc. R. Soc. B 2018, 285, 20172726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sumana, A.; Sona, C. Key relocation leaders in an Indian queenless ant. Behav. Process. 2013, 97, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charbonneau, D.; Hillis, N.; Dornhaus, A. ‘Lazy’ in nature: Ant colony time budgets show high ‘inactivity’ in the field as well as in the lab. Insectes Soc. 2015, 62, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbara, B.; Lachaud, J.-P.; Fresneau, D. Individual variability, social structure and division of labour in the ponerine ant Ectatomma ruidum Roger (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Ethology 1989, 82, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbonneau, D.; Dornhaus, A. Workers “specialized” on inactivity: Behavioral consistency of inactive workers and their role in task allocation. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2015, 69, 1459–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Maechler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Core Team, R. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2019; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Jessen, K.; Maschwitz, U. Orientation and recruitment behavior in the ponerine ant Pachycondyla tesserinoda (Emery): Laying of individual-specific trails during tandem running. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1986, 19, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschwitz, U.; Jessen, K.; Knecht, S. Tandem recruitment and trail laying in the ponerine ant Diacamma rugosum: Signal analysis. Ethology 1986, 71, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölldobler, B.; Janssen, E.; Bestmann, H.J.; Leal, I.R.; Oliveira, P.S.; Kern, F.; König, W.A. Communication in the migratory termite-hunting ant Pachycondyla (=Termitopone) marginata (Formicidae, Ponerinae). J. Comp. Physiol. A 1996, 178, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, K.J.; Harman, K.; Villet, M.H. Recruitment behaviour in the ponerine ant, Plectroctena mandibularis F. Smith (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Afr. Entomol. 2006, 14, 367–372. [Google Scholar]

- Hölldobler, B. Recruitment behavior in Camponotus socius (Hym. Formicidae). Z. vergl. Physiol. 1971, 75, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölldobler, B.; Obermayer, M.; Alpert, G.D. Chemical trail communication in the amblyoponine species Mystrium rogeri Forel (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Ponerinae). Chemoecology 1998, 8, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, G.S.B.; Wong, A.M.; Hergarden, A.C.; Wang, J.W.; Simon, A.F.; Benzer, S.; Axel, R.; Anderson, D.J. A single population of olfactory sensory neurons mediates an innate avoidance behaviour in Drosophila. Nature 2004, 431, 854–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X. Modular genetic control of innate behaviors. Bioessays 2013, 35, 421–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giurfa, M.; Núñez, J.; Chittka, L.; Menzel, R. Colour preferences of flower-naive honeybees. J. Comp. Physiol. A 1995, 177, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbert, A. Color choices by bumble bees (Bombus terrestris): Innate preferences and generalization after learning. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2000, 48, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuschen, B.; Gumbert, A.; Lunau, K. A generalised mimicry system involving angiosperm flower colour, pollen and bumblebees’ innate colour preferences. Plant Syst. Evol. 2005, 252, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulson, D.; Cruise, J.L.; Sparrow, K.R.; Harris, A.J.; Park, K.J.; Tinsley, M.C.; Gilburn, A.S. Choosing rewarding flowers; perceptual limitations and innate preferences influence decision making in bumblebees and honeybees. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2007, 61, 1523–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, J. Imprinting: The interaction of learned and innate behavior: II. The critical period. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1957, 50, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caubet, Y.; Jaisson, P.; Lenoir, A. Preimaginal induction of adult behaviour in insects. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. B 1992, 44, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pérez, J.A. Ant-plant relationships; environmental induction by early experience in two species of ants: Camponotus vagus (Formicinae) and Crematogaster scutellaris (Myrmicinae). Folia Entomol. Mex. 1987, 71, 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Morillo, I.M.; Carnevali Fernández-Concha, G.; Chi-May, F. Guía Ilustrada de las Bromeliaceae de la porción Mexicana de la Península de Yucatán; Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán-PNUD: Mérida, México, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- de Omena, P.M.; Kersch-Becker, M.F.; Antiqueira, P.A.P.; Bernabé, T.N.; Benavides-Gordillo, S.; Recalde, F.C.; Vieira, C.; Migliorini, G.H.; Romero, G.Q. Bromeliads provide shelter against fire to mutualistic spiders in a fire-prone landscape. Ecol. Entomol. 2018, 43, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, E.H.; Massarioli, A.P.; Moreno, I.A.M.; Souza, F.V.D.; Ledo, C.A.S.; Alencar, S.M.; Martinelli, A.P. Volatile compounds profile of Bromeliaceae flowers. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2016, 64, 1101–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Omena, P.M.; Romero, G.Q. Fine-scale microhabitat selection in a bromeliad-dwelling jumping spider (Salticidae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2008, 94, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejean, A.; Compin, A.; Leponce, M.; Azémar, F.; Bonhomme, C.; Talaga, S.; Pelozuelo, L.; Hénaut, Y.; Corbara, B. Ants impact the composition of the aquatic macroinvertebrate communities of a myrmecophytic tank bromeliad. C. R. Biol. 2018, 341, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nottingham, S.F.; Hardie, J.; Dawson, G.W.; Hick, A.J.; Pickett, J.A.; Wadhams, L.J.; Woodcock, C.M. Behavioral and electrophysiological responses of aphids to host and nonhost plant volatiles. J. Chem. Ecol. 1991, 17, 1231–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.X.; Kang, L. Role of plant volatiles in host plant location of the leafminer, Liriomyza sativae (Diptera: Agromyzidae). Physiol. Entomol. 2002, 27, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, T.J.A.; Wadhams, L.J.; Woodcock, C.M. Insect host location: A volatile situation. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 10, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heil, M. Indirect defence via tritrophic interactions. New Phytol. 2008, 178, 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turlings, T.C.J.; Tumlinson, J.H.; Lewis, W.J. Exploitation of herbivore-induced plant odors by host-seeking parasitic wasps. Science 1990, 250, 1251–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hilker, M.; Kobs, C.; Varama, M.; Schrank, K. Insect egg deposition induces Pinus sylvestris to attract egg parasitoids. J. Exp. Biol. 2002, 205, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Liu, Z.; Sun, J. Olfactory cues in host and host-plant recognition of a polyphagous ectoparasitoid Scleroderma guani. BioControl 2015, 60, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rocha, F.H.; Lachaud, J.-P.; Hénaut, Y.; Pozo, C.; Pérez-Lachaud, G. Nest Site Selection during Colony Relocation in Yucatan Peninsula Populations of the Ponerine Ants Neoponera villosa (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insects 2020, 11, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects11030200

Rocha FH, Lachaud J-P, Hénaut Y, Pozo C, Pérez-Lachaud G. Nest Site Selection during Colony Relocation in Yucatan Peninsula Populations of the Ponerine Ants Neoponera villosa (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insects. 2020; 11(3):200. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects11030200

Chicago/Turabian StyleRocha, Franklin H., Jean-Paul Lachaud, Yann Hénaut, Carmen Pozo, and Gabriela Pérez-Lachaud. 2020. "Nest Site Selection during Colony Relocation in Yucatan Peninsula Populations of the Ponerine Ants Neoponera villosa (Hymenoptera: Formicidae)" Insects 11, no. 3: 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects11030200